TL;DR#

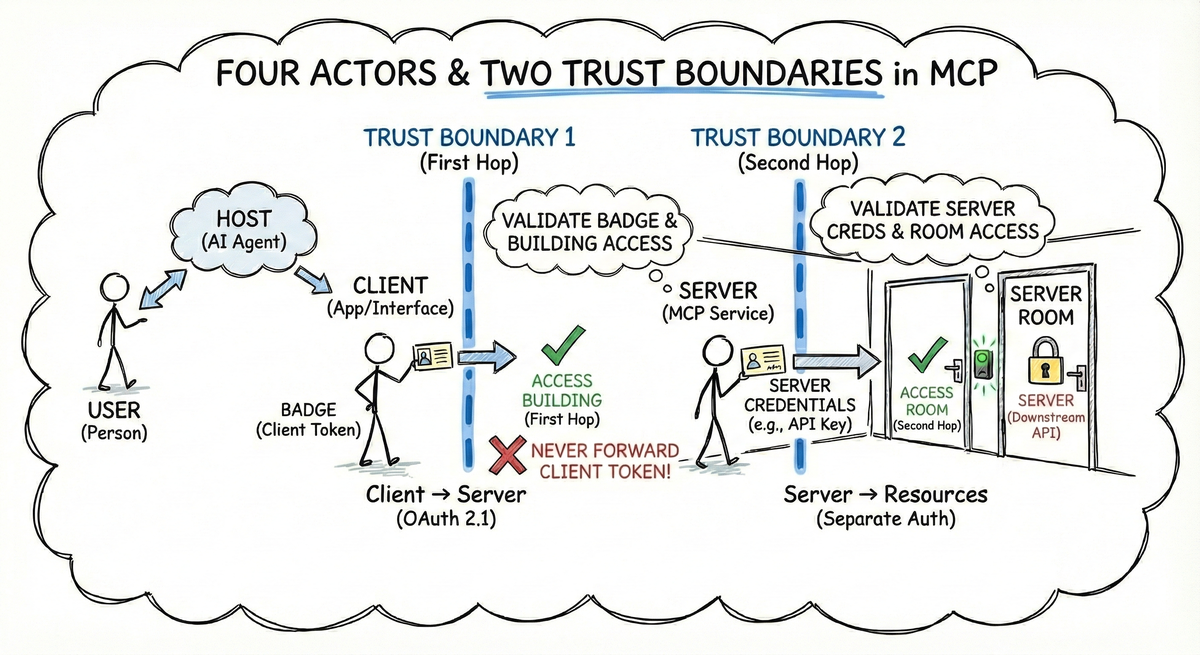

- MCP involves four actors (User, Host, Client, Server)

- Two trust boundaries matter: the first hop (Client → Server, your responsibility via OAuth 2.1) and the second hop (Server → Resources, separate auth per API)

- Never forward client tokens to downstream APIs—your MCP server should obtain its own credentials for each resource

- MCP’s autonomous agent model (the Host reasons about which tools to call) creates prompt injection risks beyond traditional APIs

- Clear trust boundaries are the foundation—without them, your server can’t distinguish legitimate requests from imposters

1. Introduction: The Universal Connector#

In our 4-part introduction to MCP, we described MCP as USB-C for AI—a universal connector that lets you build an integration once and use it anywhere. That’s the connector standard solved.

But MCP has an even more ambitious vision layered on top: UPnP for AI applications. Just as Universal Plug and Play lets any device automatically discover and connect to any other device on a network, MCP aims to let any AI client discover and connect to any MCP server without prior coordination.

USB-C solved the “write once, run everywhere” problem. UPnP-style discovery solves the “plug in anything, anywhere” problem. And that’s where things get complicated.

As Paul Carleton from Anthropic explains at the MCP Developers Summit EU 2025:

“MCP strives for UPnP for AI applications—any client can connect to any server without prior coordination. But this cuts against the grain of traditional OAuth patterns: users pick servers their client developer has never heard of, creating unique security challenges.” 1

The result? Authentication in MCP requires a fundamentally different way of thinking about trust. Without clear trust boundaries, your MCP server can’t distinguish between you and someone pretending to be you.

In this series, we’ll explore the trust model that makes MCP authentication work for MCP server developers. You’ll learn who talks to whom, where trust boundaries live, and how to implement auth in your MCP servers with confidence.

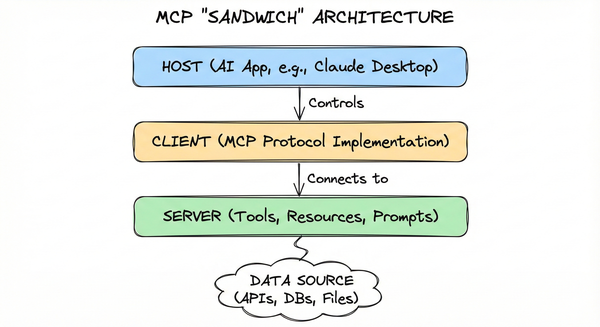

2. Meet the Players: Four Actors in Every MCP Transaction#

Before diving into trust boundaries, we need to understand who’s actually talking to whom. Every secure MCP transaction involves four distinct actors, each playing a specific role in the trust chain.

graph TD

User["👤 User

The human who wants to accomplish tasks"]

subgraph Host["💻 Host

Claude Desktop, Cursor, VS Code"]

Client["🔌 MCP Client

Library that speaks MCP protocol"]

end

Server["🖥️ MCP Server

Exposes tools/resources/prompts"]

User -->|Uses| Host

Client -->|Connects via MCP| Server

The User is you—the human sitting at the keyboard, asking questions and granting permissions. You’re the source of truth for who should have access to what.

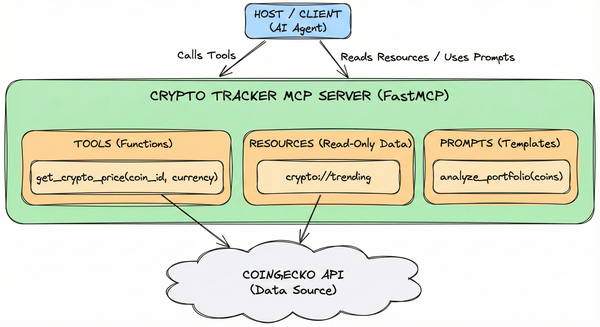

The Host is the application you’re using: Claude Desktop, Cursor, VS Code, or any AI app that supports MCP. The Host provides the user interface and contains an MCP Client implementation.

The MCP Client is the library that speaks the MCP protocol. It handles the technical details: initiating connections, managing authentication tokens, and routing messages between the Host and Server.

The MCP Server is the tool you’re connecting to—exposing resources like database records, tools like executable functions, or prompts for reusable interactions. A Google Calendar MCP Server, a GitHub integration, or your internal documentation system are all examples.

Here’s the sequence in action when you ask Claude to create a GitHub issue:

sequenceDiagram

participant User

participant Host

participant Client

participant Server

User->>Host: "Create a GitHub issue"

Host->>Client: Find MCP servers

Client->>Server: Discover available tools

Server-->>Client: Here are my tools

Client->>Server: Request authentication

User->>Host: Grant permission

Host->>Client: Provide credentials

Client->>Server: Call create_issue tool

Server-->>Client: Issue created

Client-->>Host: Result

Host-->>User: "Issue #123 created"

Key insight: The Client speaks on your behalf to the Server. This delegation is what makes MCP powerful—and what makes authentication challenging.

3. The Two-Hop Problem: Where Trust Breaks Down#

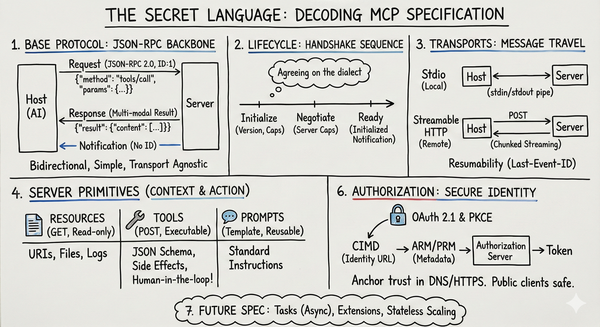

When your MCP server receives a request, it’s actually sitting at the midpoint of two distinct authentication flows. Understanding this distinction is critical because the two hops have completely different security models—both are your responsibility as an MCP server developer, but only the first hop is governed by the MCP specification.

graph LR

subgraph "First Hop (MCP Spec)"

Client["🔌 MCP Client"] -->|"OAuth 2.1

Governed by MCP"| Server["🖥️ MCP Server"]

end

subgraph "Second Hop (Not MCP)"

Server["🖥️ MCP Server"] -->|"Separate auth per API"| Backend["🗄️ Backend APIs

Google, Slack, DB, etc."]

end

The first hop—MCP Client to MCP Server—is what the MCP specification governs. When Claude Desktop connects to your server, it needs to prove that it’s acting on behalf of an authorized user. This flow uses OAuth 2.1, and the MCP spec defines exactly how it should work. This is your responsibility as an MCP server developer—the MCP specification provides the OAuth 2.1 pattern to follow.

The second hop—MCP Server to downstream APIs—is also your responsibility as an MCP server developer, but it isn’t governed by MCP at all. Once your server receives a request, it may need to call GitHub’s API, query a database, or reach out to Slack. Each of these connections has its own authentication requirements that you must implement separately.

As Wils Dawson from Arcade explains:

“There are two distinct types of OAuth in MCP. Number one is client to server, where the MCP client is authenticating to the MCP server. The basics are in the spec. Number two is server to downstream APIs, where the MCP server is authenticating to Google, Dropbox, etc.” 2

UPnP solves the problem of finding the room, but it doesn’t solve the problem of unlocking the door. For that, we need a different model: the office badge.

Think of it like an office badge system. Your badge gets you into the building and onto specific floors (first hop)—that’s the MCP protocol’s job. But once you’re in the secure area, each room has its own access control (second hop). The badge system doesn’t know about the retina scanner for the server room, and it doesn’t need to. Your MCP server is like that secure room: it controls who gets in, but what happens inside is up to you.

The danger zone is conflating these two hops. As Paul Carleton from Anthropic notes:

“This first hop is from the MCP client to the MCP server. We have our authorization server for that connection that’s well defined in the specification… This second hop to these other servers is not really under the governance of MCP at all.” 1

When someone asks “how do I do OAuth in MCP?”, the first question should always be: which hop are you talking about?

4. Trust Boundaries: Where Do You Draw the Lines?#

A trust boundary is any point where data or control crosses between security domains. On one side, a trusted entity verifies identity and permissions. On the other, a different entity makes its own decisions about what to allow. As an MCP server developer, you need to worry about exactly two trust boundaries—the ones that involve your server. Both are your responsibility, but they work differently.

graph LR

subgraph "External: Not Your Concern"

UserHostClient["👤 User + 💻 Host + 🔌 Client

You see these as one entity"]

end

subgraph "Boundary 1: First Hop"

UserHostClient ==>|"OAuth 2.1

Governed by MCP"| Server["🖥️ MCP Server"]

end

subgraph "Boundary 2: Second Hop"

Server ==>|"Separate auth per API"| Resources["🗄️ Resources

(Also YOUR responsibility

via separate auth)"]

end

linkStyle 0 stroke:#ff0000,stroke-width:3px,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

linkStyle 1 stroke:#ff0000,stroke-width:3px,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

From your MCP server’s perspective, the User, Host, and Client are all on the “outside.” You don’t need to implement the login screen for the User. You rely on the token passed by the Client to verify that authentication happened. You don’t worry about how the Host contains the Client, or how the User proved their identity to Anthropic. You see one entity making requests: the MCP Client (acting on behalf of a User).

Boundary 1: Client to Server is your first responsibility as an MCP server developer. The MCP Client needs to prove it’s acting on behalf of an authorized user. This is the first hop that the MCP specification governs, using OAuth 2.1 patterns. Your server validates tokens, checks scopes, and decides whether to accept or reject requests.

As the MCP authorization specification states:

“A protected MCP server acts as an OAuth 2.1 resource server, capable of accepting and responding to protected resource requests using access tokens.” 3 “The authorization server is responsible for interacting with the user (if necessary) and issuing access tokens for use at the MCP server. The implementation details of the authorization server are beyond the scope of this specification.”3

You’re not verifying the user’s identity yourself—that’s handled by an external authorization server like Okta, Auth0, or an enterprise IdP. Your job as MCP server developer is to validate that the token presented by the Client, was issued by a trusted authorization server and grants the appropriate permissions.

Boundary 2: Server to Resources is the second hop—where your MCP server connects to downstream APIs, databases, or services. This boundary isn’t governed by MCP at all. If your server talks to Google Calendar, GitHub, or an internal database, each connection has its own authentication requirements.

A critical security principle applies here: don’t pipe credentials through. As Paul Carleton warns,

you shouldn’t “use the same token and pass it straight through to that other resource server because you end up with token leakage risks.” 1.

Your MCP server should obtain its own tokens for downstream APIs, not forward the token it received from the client.

Think of it like that office building. The front desk, elevators, and lobby are all managed by someone else—that’s the User/Host/Client domain. You’re the secure department on floor 42. You have a badge reader at your door (Boundary 1), and you control what happens inside your office (Boundary 2). You don’t worry about how visitors got into the building—you just verify they have the right badge before letting them in.

Without these clear boundaries, your MCP server can’t distinguish between legitimate requests and imposters. Each boundary is a line of defense, and understanding where they sit is the foundation of secure MCP implementation.

5. What Makes MCP’s Trust Model Unique#

MCP isn’t just another API standard. The difference lies in what happens between the Client and your MCP Server.

Traditional APIs work like this: a client makes a specific request to a specific endpoint, and the server responds. The client decides what to ask for, and the server decides whether to grant it. But in MCP, the Client isn’t just forwarding requests—it’s reasoning about which tools to call, in what order, with what parameters.

The Host (like Claude Desktop) contains an AI model that autonomously decides to call your MCP server’s tools based on the user’s request. It might call multiple tools in sequence, combine results, or retry with different parameters. This autonomy is what makes MCP powerful, but it also creates unique security considerations.

As Simon Willison explains, this creates vulnerability to prompt injection—where malicious data tricks the AI into making unintended tool calls:

“Any time you mix together tools that can perform actions on the user’s behalf with exposure to potentially untrusted input you’re effectively allowing attackers to make those tools do whatever they want.” 4

Your MCP server needs to be prepared for an autonomous agent calling it—not just a human clicking buttons. The AI might call your tools in unexpected ways, at unexpected times, with parameters you didn’t anticipate. Traditional API security patterns assume a human is in the loop somewhere. In MCP, the loop is different.

This doesn’t mean your server is defenseless. Token validation, scopes, and proper authorization still work. But it does mean you need to think about security differently. We’ll dive deeper into these threats in the next post.

For now, you have the foundation: you understand who talks to whom, where trust boundaries live, and what makes MCP’s architecture unique. The next question is: who are you, and what can you do? That’s the difference between authentication and authorization—and the topic of our next post.

Key Takeaways#

Four actors participate in every MCP transaction: User, Host, Client, and Server. From your MCP server’s perspective, the User/Host/Client are one external entity making requests.

Two trust boundaries matter for MCP server developers: the first hop (Client → Server, governed by MCP’s OAuth 2.1 spec) and the second hop (Server → Resources, separate auth per API that you implement).

The first hop is your responsibility as an MCP server developer—you validate tokens, check scopes, and decide whether to accept requests from MCP clients, following the OAuth 2.1 pattern defined by MCP.

The second hop is also your responsibility—it requires separate tokens for each downstream API. Never forward the client’s token to downstream APIs. Your server should obtain its own credentials for each resource it accesses.

MCP’s autonomous agent model creates unique security considerations. The Host’s AI reasons about which tools to call, not just forwarding requests, which introduces prompt injection risks beyond traditional APIs.

Clear trust boundaries are the foundation. Without them, your server can’t distinguish between legitimate requests and imposters.

References#

Paul Carleton. “Why is MCP Auth Hard and What Are We Planning to Do About It.” MCP Developers Summit EU 2025. London, UK. October 2, 2025. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Wils Dawson. “MCP Authentication: The Confusing Parts Explained.” Arcade. July 8, 2025. ↩︎

Model Context Protocol. “Authorization.” Official MCP Documentation. ↩︎ ↩︎

Simon Willison. “Model Context Protocol has prompt injection security problems.” Simon Willison’s Blog. April 9, 2025. ↩︎