TL;DR#

- Authentication answers “who are you?"—proving identity via a trusted authorization server

- Authorization answers “what can you do?"—checking whether a token grants permission for specific operations

- OAuth defines four roles that map cleanly to MCP: Resource Owner (User), Client (MCP Client), Authorization Server (external IdP), and Resource Server (your MCP Server)

- Tokens are self-contained permission slips that must be validated before use—signature, expiration, audience, issuer, and scope all matter

- Scopes implement least privilege—granting minimum necessary access, like a valet key that can start the car but can’t open the trunk

- MCP provides the specification for auth flows and metadata endpoints, but you implement token validation, scope checking, and business logic

1. Introduction: The Two Questions Every Secure System Must Answer#

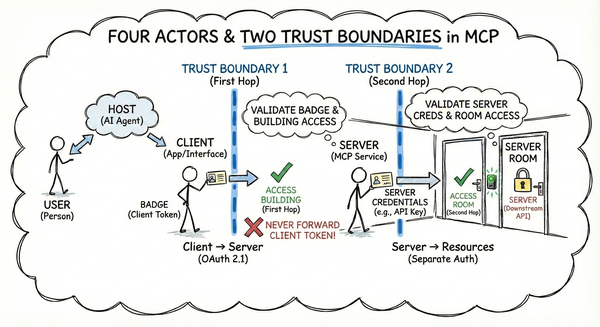

In part 1, we explored the trust model underpinning MCP—four actors, two trust boundaries, and why the first hop (Client to Server) is your responsibility. Now: how do you implement that hop?

Part 1 established where the trust boundaries are drawn. This part explains the language spoken across those boundaries.

Every secure system must answer two fundamental questions:

- Who are you?—Authentication, proving identity

- What can you do?—Authorization, granting permissions

These are distinct—answering one doesn’t answer the other. A server that verifies identity but can’t distinguish read from write is like a valet who can also open your trunk: technically trustworthy, but over-privileged.

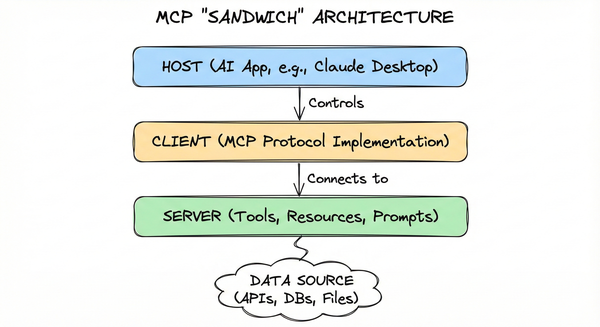

MCP uses OAuth 2.1 to answer these questions—a standardized authorization flow working across identity providers, AI hosts, and MCP servers. But OAuth is complex, and MCP’s autonomous agent model creates unique challenges.

In this post, we’ll map OAuth’s concepts to MCP’s architecture, explain how tokens and scopes work, and clarify what the MCP specification provides versus what you implement yourself.

2. Authentication vs Authorization: The Distinction That Matters#

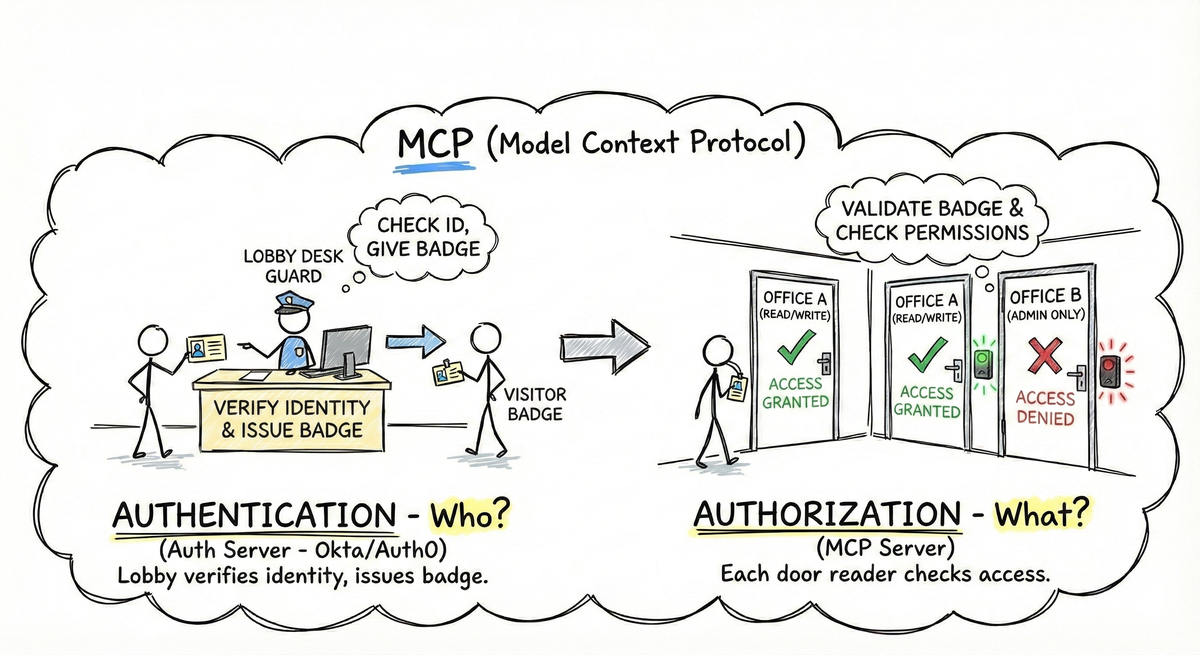

The distinction is simple but frequently conflated—both are required for a secure MCP server.

Authentication answers “who are you?"—proving identity via a trusted authorization server. Authorization answers “what can you do?"—checking permission for the specific operation requested.

These are separate layers. The user logs in once to get a token (Authentication), but your server validates that token on every single request to ensure permission (Authorization). Each tool call requires a permission check.

Why it matters: a server that verifies identity but can’t distinguish “read” from “write” might let anyone in, but won’t know what they’re allowed to do. Conversely, a server that checks permissions without verifying identity can’t enforce per-user access controls.

As FastMCP explains:

“Token validation separates authentication (proving who you are) from authorization (determining what you can do). Your MCP server receives proof of identity in the form of a signed token and makes access decisions based on the claims within that token.” 1

In MCP, the authorization server (Okta, Auth0) handles authentication—verifying user identity and issuing tokens. Your MCP server handles authorization—validating tokens and checking permissions. Think of an office building: the lobby desk verifies identity (authentication) and issues a badge, but each office door has a reader checking access (authorization). Both are necessary.

3. OAuth Roles and How They Map to MCP#

OAuth 2.1 defines four roles that describe authorization flow entities. These are functions, not physical servers—one system can play multiple roles.

graph TD

User["👤 User / Resource Owner

(You)"]

Client["🔌 MCP Client / OAuth Client

(Claude Desktop)"]

AS["🔐 Authorization Server

(Auth0 / Okta)"]

Server["🖥️ MCP Server / Resource Server

(Your Weather MCP)"]

User -->|Authenticates to| AS

Client -->|Obtains token from| AS

Client -->|Presents token to| Server

Server -->|Validates token against| AS

The Resource Owner is the User—the human owning the data who decides access permissions. In MCP, this is the person using Claude Desktop, Cursor, or VS Code.

The Client is the application requesting access—the MCP Client library embedded in the Host (like Claude Desktop). It handles obtaining tokens and presenting them to your MCP Server.

The Authorization Server is the external service handling authentication and issuing tokens (Okta, Auth0, Scalekit, etc.). It verifies user identity and mints tokens proving this verification occurred.

The Resource Server is your MCP Server—the protected resource clients want to access. Your server validates tokens and grants or denies requests based on encoded permissions.

A critical nuance: OAuth roles are functions, not physical servers. Many services combine Authorization Server and Resource Server (Google’s OAuth both issues and validates tokens). In MCP, these roles are deliberately separated: the Authorization Server is an external IdP, while your MCP Server acts purely as a Resource Server.

As Scalekit explains:

“Scalekit OAuth authorization server acts as the identity provider for your MCP server… Your MCP Server validates incoming access tokens and enforces the permissions encoded in each token.” 2

This separation lets your MCP server focus on business logic while the Authorization Server handles authentication complexity. From Post 1’s perspective, the first hop (Client to Server) is where these roles interact—the Client obtains a token and presents it to your Server for validation.

4. Tokens: The Permission Slip#

We’ve distinguished authentication from authorization. Now let’s see how these work in practice: token validation and scope checking.

Tokens bridge authentication and authorization. When a user authenticates with the Authorization Server, it issues a token—a self-contained permission slip proving identity and encoding permissions. The MCP Client presents this token to your server, which validates it to decide whether to grant access.

Think of a token like a hotel key card—encoded with room number, check-out date, and access permissions. Each door reader validates the card without calling the front desk. When it expires, it stops working everywhere. If lost, whoever finds it has access until reported missing—exactly why short-lived tokens matter.

In OAuth 2.1, tokens are typically bearer tokens in JSON Web Token (JWT) format, transmitted in the Authorization header:

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCIgOiAiSldUIiw...A bearer token works like cash: whoever holds it can spend it. The token contains cryptographically signed claims that your server validates without contacting the Authorization Server.

graph LR

Token[Access Token]

Sig[Signature

Valid?]

Exp[Expiration

Valid?]

Aud[Audience

Matches?]

Iss[Issuer

Trusted?]

Scope[Scope

Sufficient?]

Grant[Grant Access]

Token --> Sig

Sig -->|Yes| Exp

Exp -->|Yes| Aud

Aud -->|Yes| Iss

Iss -->|Yes| Scope

Scope -->|Yes| Grant

Your MCP server must validate five claims before accepting any request: signature (signed by trusted server), expiration (typically 5-60 minutes), audience (intended for your server), issuer (from trusted IdP), and scope (grants required permission).

As the MCP documentation notes:

“Use short-lived access tokens… if a malicious actor steals them, they will be able to maintain their access for longer periods” and “Always validate tokens… verify that what your MCP server is getting matches the required constraints.” 2

5. Scopes and Least Privilege#

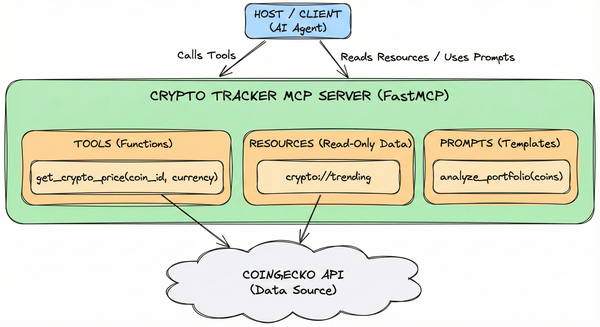

If tokens are permission slips, scopes are the specific permissions written on those slips. A scope is a string representing a particular access right—like calendar:read or files:write. Your MCP server checks scopes before executing any tool.

Your MCP server defines what scopes it requires, and clients discover these through protocol metadata. During the authorization flow, the client reads your server’s metadata to determine which scopes to request from the Authorization Server. This connects the “what” (scopes as permissions) to the “how” (protocol mechanics for discovery).

This connects directly to Section 2’s framework: if token validation answers “who are you?”, scope checking answers “what can you do?"—this is the authorization layer in action.

Scopes implement the principle of least privilege: granting only the minimum access necessary. Common MCP scope patterns include mcp:tools (generic access), mcp:tools:read (read-only), and resource-specific scopes like todo:read, todo:write.

Why this matters: a task management MCP might expose both safe tools (reading public lists) and sensitive tools (deleting tasks). If all tools require the same broad scope, any client can do everything. Scopes let you distinguish harmless from destructive operations.

The MCP documentation recommends:

“Don’t use catch-all scopes. Split access per tool or capability where possible and verify required scopes per route/tool on the resource server.” 2

Scalekit’s documentation adds:

“Add scope validation at the MCP tool execution level to ensure tools are only executed when the user has authorized the MCP client with the required permissions. This provides fine-grained access control and follows the principle of least privilege.” 3

Think of scopes like a valet key—starts the car and unlocks the driver’s door, but can’t open the glove box or trunk. A server that can’t distinguish “read” from “write” is like a valet who can also open your trunk: technically convenient, but unnecessary and risky.

6. What MCP Provides vs What You Implement#

A common confusion: what does MCP actually provide versus what must you implement? The MCP spec defines protocols and formats, but doesn’t provide implementations—you still write code that validates tokens and enforces permissions.

MCP provides: the authorization flow specification, metadata endpoints like .well-known/oauth-protected-resource, protocol formats for token transmission, and integration with OAuth 2.1 standards.

You implement: token validation (checking signatures, expiration, audience, issuer, scopes), scope enforcement (mapping tools to required permissions), business logic, and integration with your chosen Authorization Server. Don’t roll your own crypto—use established Python libraries like python-jose or PyJWT to handle validation.

The MCP documentation is explicit:

“The MCP server now serves as a resource server that validates tokens and provides metadata about its protected resources, while relying entirely on external authorization servers for authentication and authorization.” 2

MCP doesn’t provide an Authorization Server—you bring your own (Okta, Auth0, Scalekit, Keycloak). Your choice affects how users authenticate, but your validation logic remains the same.

FastMCP’s documentation explains:

“Token validation works well when you already have authentication infrastructure that can issue structured tokens like JWTs. Your existing API gateway, microservices platform, or enterprise SSO system becomes the source of truth for user identity, while your MCP server focuses on its core functionality.” 1

Think of it like HTTP: the spec defines how clients and servers exchange messages, but you write the application logic. MCP gives you the OAuth language—you implement the conversation. We’ll cover implementation details in Posts 5 and 6.

7. Key Takeaways#

We’ve covered the conceptual landscape of authentication and authorization in MCP. Here’s the foundation:

Authentication and authorization are distinct but complementary. Authentication proves “who are you” via a trusted Authorization Server. Authorization determines “what can you do” by checking token permissions. Both are necessary—neither is sufficient alone.

OAuth roles map cleanly to MCP. The User is the Resource Owner, the MCP Client is the OAuth Client, an external IdP is the Authorization Server, and your MCP Server is the Resource Server. Understanding these roles clarifies where your responsibilities begin and end.

Tokens are validated, not just accepted. Every request must validate signature, expiration, audience, issuer, and scope. Short-lived tokens limit theft damage, and audience validation prevents tokens meant for one service from being used against another.

Scopes implement least privilege. Granular scopes like calendar:read and tasks:write grant minimum necessary access. The valet key captures this: works for the job at hand, but can’t access everything.

MCP provides the spec, you provide the implementation. MCP defines protocols and formats; you implement token validation, scope enforcement, and business logic. You choose the Authorization Server, and your server validates whatever tokens it issues.

These concepts form the foundation for secure MCP servers. In Post 3, we’ll explore deployment scenarios from personal projects to enterprise environments. Posts 4 through 6 will cover threats, implementation details, and production-ready patterns.

References#

FastMCP. “Authentication.” Documentation. ↩︎ ↩︎

Model Context Protocol. “Understanding Authorization in MCP.” Official MCP Documentation. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Scalekit. “Add OAuth 2.1 authorization to MCP servers.” December 15, 2025. ↩︎