TL;DR#

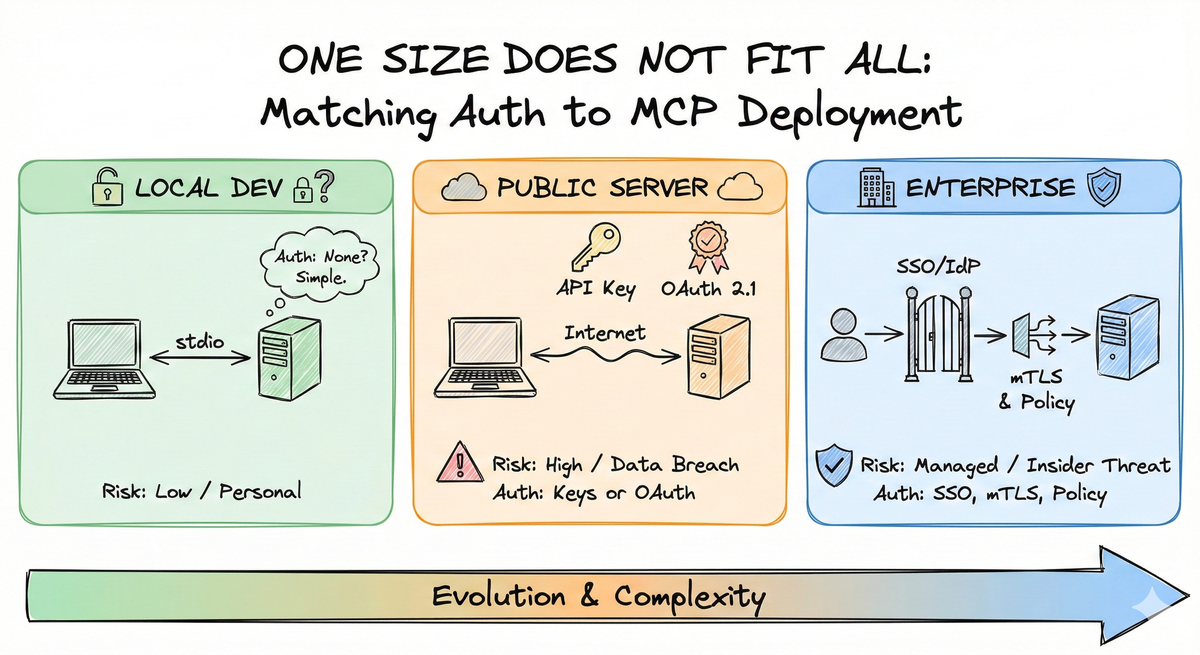

- Three MCP deployment scenarios require different auth approaches: local development (minimal), public servers (API keys or OAuth 2.1), and enterprise (SSO, mTLS)

- Start with scenario, not solution—ask where your server will run and who will use it before choosing auth

- Local stdio limits exposure but is not a security boundary—local HTTP servers can still be misconfigured

- Public servers need positive identification—API keys don’t carry user identity

- Enterprise requires SSO integration—don’t build OAuth authorization servers when the IdP already exists

1. Introduction: Scenario Before Solution#

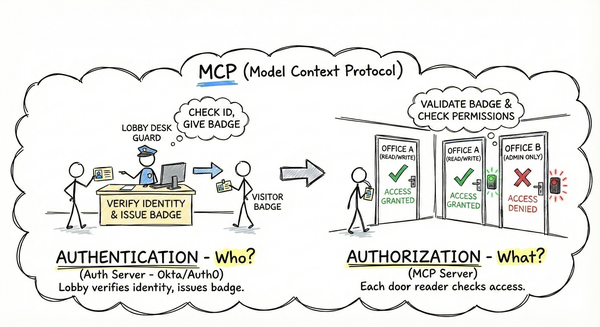

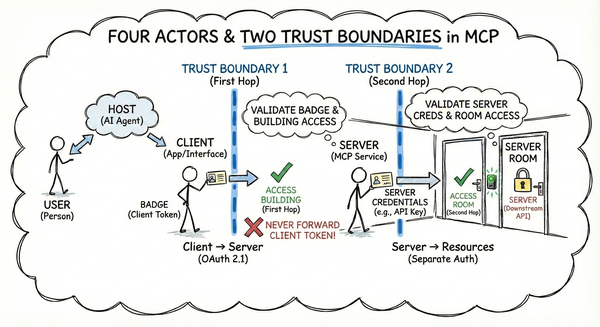

Part 1 established the MCP trust model: four actors, two trust boundaries, and why the first hop is your responsibility. Part 2 mapped auth to OAuth 2.1—tokens, scopes, and what MCP provides versus what you implement.

Now the practical question: which auth approach fits your situation?

Deploying an enterprise-grade OAuth flow for a local script is a productivity killer; deploying a public server with a hardcoded API key is a data breach waiting to happen.

This is where developers go wrong. They see enterprise posts describing OAuth 2.1 flows, mutual TLS, and SSO—then implement all of it for a localhost server. Or worse, they ship a public server protected by a hardcoded API key.

The consequences are real. Under-protect a public server, and anyone drains your quota or accesses another user’s data. Over-protect a local tool, and you’ve wasted days on enterprise auth for something only you will use.

This part maps three deployment scenarios—local development, public servers, and enterprise—to appropriate auth strategies. You’ll see what happens when you choose poorly, and you’ll leave with a decision framework for matching auth to deployment.

2. The Three Scenarios#

MCP servers run in fundamentally different environments. The key differentiator is threat model plus infrastructure—who are your attackers, what’s at stake, and what defenses you have.

graph TD

subgraph Enterprise["Enterprise"]

E1["Transport: HTTP/SSE"]

E2["Network: Restricted"]

E3["Threat: Insider + external"]

E4["Auth: SSO, mTLS"]

end

subgraph Public["Public Server"]

P1["Transport: HTTP/SSE"]

P2["Network: Public internet"]

P3["Threat: Anyone, anywhere"]

P4["Auth: API keys or OAuth 2.1"]

end

subgraph Local["Local Development"]

L1["Transport: stdio"]

L2["Network: Local only"]

L3["Threat: Local process access"]

L4["Auth: Minimal"]

end

style Local stroke:#1b5e20,stroke-width:2px

style Public stroke:#e65100,stroke-width:2px

style Enterprise stroke:#01579b,stroke-width:2px

graph TD

subgraph Local_Trust["Local Development: Process-Level Boundary"]

L1[Your Machine]

L2[Stdio MCP Server]

L3[MCP Client]

L1 --- L2 --- L3

end

subgraph Public_Trust["Public Server: No Network Boundary"]

P1[Anonymous Internet]

P2[Your MCP Server]

P3[Legitimate Users]

P1 --> P2 --> P3

P1 -.->|Attackers| P2

end

style Local_Trust stroke:#1b5e20,stroke-width:2px

style Public_Trust stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px

The Trust Boundary Difference: Local stdio servers have a natural boundary—only code running on your machine can invoke them. Public HTTP servers have no inherent boundary; anyone on the internet can reach your endpoint. This is why public servers need auth and local servers often don’t.

- Local Development runs via stdio or local HTTP with different risk profiles. The stdio transport uses standard input/output pipes—no network exposure—but executes arbitrary code on your machine. Local HTTP servers bind to localhost and face network risks like accidental exposure if misconfigured 1.

Critical Distinction: With stdio, your MCP server is local-only—but the client (Claude Desktop, Cursor) may still send data to the internet. The data flow is: MCP server → Client (local) → External API (Anthropic). Your stdio server doesn’t touch the network directly, but the data you process passes through a client that might.

Public Server faces the open internet. Anyone with the URL can attempt to connect. You’re defending against anonymous attackers, so API keys with rotation or OAuth 2.1 becomes essential.

Enterprise deployments live inside corporate networks with SSO integration. The threat model includes both external attackers and malicious insiders, requiring full OAuth 2.1 compliance and often mutual TLS.

3. Local Development Deep Dive#

Local development is the MCP entry point, building a server for yourself, running via stdio, testing with a local client. But stdio servers aren’t always personal tools—developers publish them as npm packages, Python wheels, or Rust crates.

The Scenario:

- Transport: stdio (standard input/output)

- Users: You, on your machine—or anyone who installs your published package

- Network: None—stdio requires local process access

- Threat model: Local process compromise, plus supply chain risk

Authentication Approach: Minimal for servers you write. For stdio servers, the risk is execution—anyone who can invoke your server already has access to your computer. For localhost HTTP servers, the transport binds to a network port, which is not a security boundary—accidental exposure remains possible 1.

Common approaches:

- No authentication: Sufficient for personal servers

- Environment variables: Simple configuration, not security

- Simple API keys: Only if distinguishing between multiple local clients

Supply Chain Risk#

When you install someone else’s MCP server locally, you’re executing arbitrary code on your machine 1:

- Credential theft: Malicious servers could read environment variables, token files, or keychains, stealing API keys for any service

- Data leakage: Servers run with your user permissions, accessing filesystem and any data you pipe through them

- No sandbox: Unlike browser extensions, stdio servers run as native processes with full user account access

Mitigation: Only run MCP servers locally from sources you trust. Review source code or use sandboxed environments (like Docker) before installation, especially for servers requiring credentials.

Quick Audit: Before Installing That MCP Server#

Before running someone else’s MCP server locally, ask three questions:

- Does this server need full filesystem access? Many servers only need to read/write specific directories. Consider running in a sandboxed environment.

- Am I passing env vars that contain production keys? If the server requires credentials, use dedicated keys with minimal scope—not your personal API tokens.

- Is the source code available for review? Closed-source servers executing arbitrary code on your machine deserve extra scrutiny. Consider sandboxed environments (like Docker) or waiting for source availability.

What Goes Wrong:

- Localhost HTTP: Binding to

0.0.0.0instead of127.0.0.1—suddenly localhost is network-reachable - Localhost HTTP: No rate limiting—buggy clients consume 100% CPU

- Any transport: Over-engineering, implementing OAuth 2.1 for a server only you will use

- Stdio: Supply chain compromise—malicious MCP servers exfiltrating API keys

When to Level Up: Move beyond local dev auth when sharing your server, exposing beyond localhost, needing audit logs, or consuming untrusted third-party servers.

4. Public Server Deep Dive#

Your MCP server deployed to a cloud provider with a URL—now anyone can connect. Authentication shifts from optional to critical.

The Scenario:

- Transport: Streamable HTTP

- Users: Anyone with the URL—intended users plus the internet

- Network: Public internet, no boundaries

- Threat model: Anonymous attackers, credential theft, data leakage between users

Authentication Approach: API keys or OAuth 2.1. HTTP means anyone can reach your endpoint—no transport-layer boundaries like stdio 2.

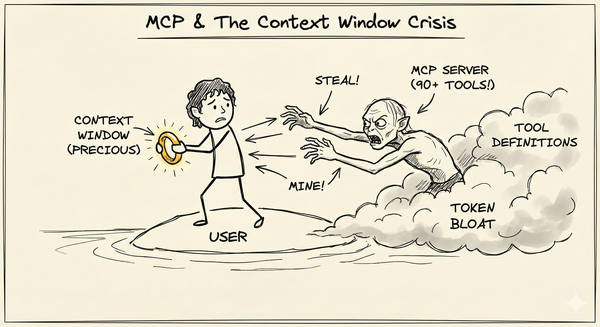

API keys are simple bearer tokens, easy but vulnerable to theft. Critically, API keys don’t carry user identity, your server can’t distinguish User A from User B without custom mapping logic.

OAuth 2.1 provides token-based authentication with refresh flows and built-in user identity, recommended for production, especially with multiple users 2.

graph TD

subgraph Threats["Public Server Threat Model"]

A[Anonymous Internet]

B[Stolen API Key]

C[User A sees User B data]

D[Quota Drain]

end

subgraph Defenses["Auth Defenses"]

E[API Key Validation]

F[OAuth 2.1 Tokens]

G[Per-User Data Isolation]

H[Rate Limiting]

end

A -.-> E

B -.-> F

C -.-> G

D -.-> H

style Threats stroke:#c62828,stroke-width:2px

style Defenses stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px

What Goes Wrong:

- No user isolation — API keys don’t identify users, User A accesses User B’s data

- Stolen keys — API keys leak in GitHub repos, draining quota. Enable secret scanning on your repos and rotate keys immediately if exposed.

- Open door — no auth means a public endpoint exposing data

- No rotation — non-expiring keys increase exposure when compromised

The Analogy: API keys are physical keys, anyone who finds one opens every door. OAuth 2.1 is like office badges, different access per person, centrally revoked, logged at every door. With keys, you can’t tell who used them.

5. Enterprise Deep Dive#

Enterprise deployments integrate with existing identity infrastructure, compliance requirements, and security policies.

The Scenario:

- Transport: HTTP/SSE inside corporate networks

- Users: Employees authenticated through company SSO

- Network: Corporate intranet, VPN, or private cloud

- Threat model: External attackers, malicious insiders, data exfiltration

Authentication Approach: SSO integration, mutual TLS, and policy engines. Enterprises already have identity providers (Okta, Entra ID, Keycloak) that issue tokens 3.

graph TD

subgraph Enterprise["Enterprise MCP Flow"]

Employee[Employee with AI Client]

IdP[Corporate SSO / IdP

Okta, Entra ID, Keycloak]

Client[MCP Client

Claude, Cursor]

Gateway[MCP Gateway / Policy Engine]

Server[MCP Server

Internal APIs, Data]

end

Employee -->|SSO Login| IdP

IdP -->|ID Token + SAML| Client

Client -->|mTLS + IdP Token| Gateway

Gateway -->|Policy Check| IdP

IdP -->|Authorization Decision| Gateway

Gateway -->|Authorized Request| Server

style Enterprise stroke:#01579b,stroke-width:2px

style IdP stroke:#f57f17,stroke-width:2px

style Gateway stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px

Typical Enterprise Approaches:

- SSO Integration: Employees authenticate once; all applications accept those tokens

- Token Exchange: The client exchanges its IdP-issued token for an MCP-specific token

- Mutual TLS: Verifying both client and server identities

- Policy Engines: Centralized authorization evaluates every request

The Gateway Pattern: This is an architecture pattern you implement—not an official MCP component. Place a proxy (Nginx, API Gateway, Envoy, or custom service) in front of your MCP server to handle mTLS termination, SSO validation, and policy enforcement. Your MCP server remains simple, accepting requests only from the trusted gateway, while the enterprise’s existing security infrastructure handles the heavy lifting. This bridges the gap between MCP’s current authorization spec and enterprise requirements.

Why This Matters: The gateway handles the OIDC/SAML dance with your IdP, so your MCP server only needs to validate a standard JWT signature. This dramatically lowers the barrier to entry for developers building internal tools—you don’t need to become an OAuth expert to build a secure enterprise MCP server. Your server validates tokens; the gateway handles everything else.

A Critical Nuance: The current MCP authorization spec is optimized for SaaS scenarios. Solo.io’s enterprise critique points out this mismatch:

“Enterprises don’t use anonymous dynamic client registration, they don’t want authorization code flows for internal apps, and they don’t want every MCP server acting as its own authorization server.” 4

Enterprises want MCP servers to be resource servers that accept IdP-issued tokens. Aaron Parecki’s “Enterprise-Ready MCP” proposes token exchange using OAuth 2.0 Token Exchange (RFC 8693) and JWT Profile for Authorization Grants (RFC 7523) 5.

What Goes Wrong:

- Over-engineering - building an OAuth authorization server when the enterprise already has one

- Shadow IT - without SSO integration, employees create workarounds that bypass security controls

- User friction - every connection requires separate OAuth 2.1 consent prompts

- Admin invisibility - direct app-to-app OAuth 2.1 connections happen behind the IdP’s back

The Analogy: A bank vault inside bank headquarters. The bank already has guards at the front door (SSO), cameras (audit logs), and policies. Your MCP server is the vault - don’t build a new front door.

6. Decision Framework#

Before implementing authentication, answer four questions:

- Who are your users? Just yourself? Trusted colleagues? Anyone on the internet?

- What’s the consequence of unauthorized access? Local inconvenience? Quota depletion? Data breach?

- Where is your server deployed? Local stdio? Public cloud? Corporate intranet?

- What auth infrastructure do you already have? Nothing? A cloud account? An enterprise SSO?

graph TD

Start[Start: What is your primary deployment target?]

Start -->|Local stdio| LocalQ{User Count?}

Start -->|Public cloud| PublicQ{Risk Level?}

Start -->|Corporate network| EnterpriseQ{SSO available?}

LocalQ-->|Just you| LResult[No auth or simple env vars]

LocalQ-->|Published package| LPResult[Check Source Trust]

PublicQ-->|Low stakes / personal| PResult[API keys]

PublicQ-->|Multi-user / data access| POResult[OAuth 2.1]

EnterpriseQ-->|Yes| EResult[SSO + IdP tokens]

EnterpriseQ-->|No| ENResult[Build IdP integration]

style LResult stroke:#1b5e20,stroke-width:2px

style LPResult stroke:#1b5e20,stroke-width:2px

style PResult stroke:#e65100,stroke-width:2px

style POResult stroke:#e65100,stroke-width:2px

style EResult stroke:#01579b,stroke-width:2px

style ENResult stroke:#01579b,stroke-width:2px

Evolution Between Scenarios: Projects change. A local tool becomes a team resource becomes a public service. Build for your current scenario, but know what’s required for the next. Local dev doesn’t need OAuth 2.1—but document that deployment requires it. Public servers can start with API keys and graduate to OAuth 2.1 as user count grows. Enterprise should always begin with SSO integration.

7. Available Approaches Summary#

| Approach | Best For | Identity Granularity | Complexity | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Local dev, stdio, personal tools | None | Minimal | N/A |

| Environment Variables | Local configuration, not security | None | Minimal | N/A |

| API Keys | Internal tools, single-user public servers | None (shared key) | Low | Data Leak / Quota Drain |

| API Keys with Rotation | Production public servers, small teams | None (shared key) | Low-Medium | Reduced exposure window |

| OAuth 2.1 | Multi-user public servers, SaaS | Per-user | Medium | Token theft, user impersonation |

| SSO / IdP Integration | Enterprise deployments | Per-user (corporate identity) | High | Insider threat |

| mTLS + Policy Engine | High-security enterprise, regulated industries | Per-user + machine identity | Very High | Advanced persistent threats |

The progression isn’t linear. Enterprise deployments skip API keys entirely for SSO. Public servers can start with API keys until user count justifies OAuth 2.1.

Match complexity to consequence. A personal bookmark server doesn’t need OAuth 2.1. A healthcare data integrator needs mTLS.

8. Key Takeaways#

Scenario identification is step one—don’t choose OAuth 2.1, API keys, or “nothing” until you’ve answered: who are your users, what are the consequences of unauthorized access, where is your server deployed, and what infrastructure do you already have?

Match auth to threat model. Enterprises need SSO because malicious insiders are real threats. Public servers need OAuth 2.1 because anonymous attackers are guaranteed. Local dev needs minimal auth because the stdio transport limits exposure.

Projects evolve between scenarios. A localhost server becomes a team tool becomes a public API. Build for today, but know what tomorrow requires.

What goes wrong when you mis-choose? Over-securing local dev wastes days. Under-securing a public server exposes user data and drains quota. Ignoring enterprise SSO creates shadow IT that gets MCP blocked entirely.

One size does not fit all. Know your scenario, choose accordingly, and evolve as needed.

Next: Part 4: MCP Threat Models and Attack Vectors examines specific attacks against MCP servers when auth is misconfigured—and how each scenario’s defenses map to those threats. We’ll cover token theft, replay attacks, supply chain compromises, and the defense-in-depth strategies that actually work.

References#

Palo Alto Networks, “MCP Security Exposed: What You Need to Know Now,” April 22, 2025. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Model Context Protocol, “Understanding Authorization in MCP,” accessed December 2025. ↩︎ ↩︎

Model Context Protocol, “Security Best Practices,” accessed December 2025. ↩︎

Solo.io, “MCP Authorization is a Non-Starter for Enterprise,” 2025. ↩︎

Aaron Parecki, “Enterprise-Ready MCP,” May 12, 2025 ↩︎